Driving Schools and the Deaf:

May 6, 2008

Glenard A. MunsonDriving Schools and the Deaf: Advice to Instructors

When a driving school gets a request to teach a deaf student to drive, one of three possible

scenarios are put into motion.

ONE, the school might refuse the student, due to a lack of a qualified instructor to work with the deaf, not realizing that this is a basic violation of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) of 1990;

TWO, the school might agree to enroll the student, only to find that the training is done piecemeal, by an unqualified instructor;

THREE, the school might actually have an instructor who is qualified, under ADA guidelines.

Sadly, the first two scenarios are the more common ones. The simple truth is that it is hard to locate a program that is geared towards teaching the deaf to drive. Part of that may be that teaching driving requires a process that is different for the deaf. This article will provide an explanation of the "differences" in the teaching process, and how driving schools can work with Deaf students.A WORD OF CAUTION: Instructors who can hear and who may speak English rather well, must suspend some of their past education regarding English syntax. Many deaf people use American Sign Language (ASL), which has a different grammar system from that of English.

Remember that Deaf and hard of hearing people tend to look at the person who is speaking or signing, (in order to see what is being said or signed and also because facial expression is also an important part of "reading" what a person is saying). Obviously, this is increases the risk factor while driving. To adjust for this you should make a habit of leaning forward a bit and doing your signs in a location where they are easy for the deaf person to understand while also keeping his eyes on the road.

Before you begin the drive, use the FOCUS ("look at") sign to remind them to look ahead. Also, plan on frequent stops to go over items in the California Driver Handbook, or other text, that the student may have problems understanding. It would also be useful to carry a "whiteboard", about the size of a 3-ring binder, to permit both of you to communicate, in writing, to each other, along with a legal pad for more permanent notes. A laptop might also be useful.

You should be aware that, just like the English language, ASL has several "dialects." As such, a person who has been trained in one ASL "dialect", may not understand YOUR dialect. For this reason, we recommend that all training begin with a one-to-two hour session (or more as needed), in a classroom environment, where you can go over the program with the student. You and the student must come to an agreement over signs, your control of the vehicle, and a complete understanding that the student is to keep his or her eyes on the road. This can be a challenge!

Remember, in order to be a safe driver, a driver needs to also be confident, and one of your main jobs, as an instructor, is to instill confidence. This is done by being knowledgeable about your subject, showing a calm and confident manner yourself (even when the student makes mistakes), and by communicating well. The only difference here is that you will be silently communicating, rather than verbally. This also means that you MUST be "on top of your game". This is NOT a job for an inexperienced instructor, or for one who doesn't like working with adults and seniors, since they present similar stress factors for the instructor.

Step One: Begin with the Instructor.

There are, basically, two ways to communicate with the deaf: ASL (American Sign Language) and SE (Signed English). In either case, a fluency in English is required. This not only means speaking, but it also means an understanding of sentence structure, words usage and modifiers of those words, and a good command of vocabulary. The last is especially important, since many “spoken” words are not easily translatable to the deaf.

Choose an instructor who fulfills these requirements before sending him/her to the world of the deaf. If the instructor has difficulty in making himself/herself understood to the hearing population, the troubles will increase when they attempt communications with the deaf. In addition, an extraordinary sense of confidence, patience, and (dare we say) courage is mandated also. If an instructor is easily frustrated when teaching the hearing, they will be inundated with stress when working with the deaf.

The above statements are NOT meant to construe the idea that the deaf are difficult or dangerous to deal with. Quite the opposite! A poor instructor becomes the danger when he or she cannot successfully communicate with ANY student, hearing-impaired or otherwise.Beginning with early grade school, most hearing people learn sentence syntax, “stressors” to inflect words, and the difference between homonyms and antonyms. When “speaking” to the deaf, many of these important lessons in spoken English are cast aside. Much of the conversation, especially when it comes to driving instruction, is done in “pidgin ASL”, where extraneous words are discarded. For example: for a hearing student, you might say, “Turn left at the next street.”, while you would sign “Next street, turn left” for the deaf student. The instructor must be able to re-direct his or her thinking into abbreviated English

ASL differs from SE by the fact that ASL attempts to convey an idea or concept located in a sentence, while SE attempts to accurately convey each word in a sentence. As an instructor, you will be using the “concept” approach, rather than the “literal” sense. The instructor must have a command of vocabulary to do this. For example, in ASL, the sign for “reverse” does NOT mean go backwards, it means the opposite of “obverse” (think of a coin…heads is the obverse, tails is the reverse). So how do you tell the deaf student to reverse 60 feet, next to a curb, for their drive test? You can't just do the sign for "back" and then "up" since the signs would be “back” (the opposite of front) and “up” (the opposite of down). In truth, since you are driving a vehicle, most deaf students will grasp the idea, since they are intelligent enough to grasp the concept that you must be “talking” about a driving situation.

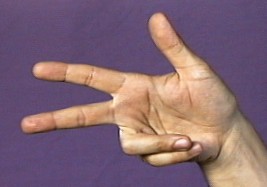

Think of different ways to say the same thing. For example, in ASL, the sign for the number 3 is often used as the sign for a vehicle. Simply making your hand into a modified “3” handshape and moving it backwards, away from the mirror, usually suffices to convey the idea of “backing up.” This is an example of a special type of signs called "classifiers." Classifiers allow you to show the direction and manner in which you want the vehicle to move.

Trust your student to understand you. They are used to struggling with the “hearing” people trying to talk to them, and in my experience, they are incredibly skilled at translating your "signs."

NOTE: The above is part of a seminar Glenard A. Munson provides for driving instructors. His interactive program includes video clips of sign language being used in a literal sense, as he speaks over the program, to explain why some may be inappropriate. He would like feedback from deaf people regarding the problems they encountered while learning to drive. Additionally he welcomes and would greatly appreciate suggestions from anyone reading this.

You may contact him at:

Glenard A. Munson

Statewide Driving School

California Driver Education Association

4441 Auburn Blvd. Suite P

Sacramento, CA 95841

916-481-5800

916-616-9993 cell

www.statewide-driving-school.com

www.mycaliforniapermit.com

www.caldriveredassn.com

driveteach@statewide-driving-school.com